From US Fish and Wildlife

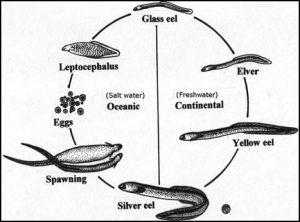

Eels have a complex lifecycle that begins far offshore in the Sargasso Sea where adults spawn.

After eggs hatch, young eels drift inland with ocean currents into streams, rivers and lakes for over 3,700 miles. This journey may take many years.

Along the way, eels metamorphose, or change, through different life stages – glass eel, elver and yellow eel, as they enter freshwater.

Young eels stay in freshwater until they reach maturity, between 10 to 25 years, before migrating back to the Sargasso Sea.

Eels hunt at night, feeding on crustaceans, small insects and other fish.

During the day, they hide among tree snags, plants, and other types of shelters found close to shore.

If I am a female, I can grow up to 4 feet in length and weigh up to 9 pounds. Males only reach 1.5 feet in length. Females also are lighter in color, with smaller eyes and higher fins than males.

Why I Matter and What’s Been Happening

My species once made up over a quarter of the total fish found in Atlantic coastal streams. Dams have prevented us from reaching our feeding grounds, and have reduced the amount of good habitat for us to live in the river. And when we migrate downstream to return to the ocean, we can get caught, and sometimes even die, in turbines at hydroelectric facilities, where electricity is generated using river water.

American Eels have a fascinating and complicated life cycle. American eels spawn only once during their life span, and the entire population spawns together in the Sargasso Sea located south of Bermuda. The leaf-shaped eel larvae (called leptocephali) drift on North Atlantic currents for up to one year before reaching coastal waters. They then metamorphose into a life stage where they are transparent and are called glass eels. Leaving the open ocean, they enter sheltered salt-water bays, brackish estuaries or freshwater rivers and begin taking on colour. At this life stage, they are called elvers. Once settled into their rearing habitats, fully pigmented elvers become yellow eels. When eels prepare for their spawning migration, they metamorphose into silver eels.

The American eel has only one single breeding population. If they are declining in one area, even if declines are not evident elsewhere, the population overall will be in decline. It is of concern that the recruitment of eels in the Upper St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes in Canada has declined by over 99 percent.

Scientists suspect the largest threats to the American eel relate to habitat quality, fishing and obstacles to their migration. This includes changes made by humans to their habitats, dams, over fishing, changes in ocean conditions, as well as acid rain and contaminants. Still, much needs to be learned about this species to help reverse the effects of such threats.

COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American Eel in Canada

Generation time for eels residing in fresh water is as high as 22 years. Generation time is much shorter in eels that reside permanently in salt water (roughly 9 years).

Population Sizes and Trends

Times series data used to estimate percent change in indices of abundance from the 1950s to the 2000s (three generations) were almost uniformly negative (from -7.1% to -96.2%) within the western portion of the species’ range, while trends were mixed within the eastern portion of its range. Indices of abundance from fishery landings series indicated negative change. Abundance relative to the 1980s is very low for Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River fish according to fisheries-independent data. Between 1996-1997 and 2010, estimates of the total number of maturing eels declined by 65% in the Great Lakes and upper St. Lawrence River area, despite the reduction in mortality from commercial fisheries (50% of fishing effort between 2002-2009). An index of year class strength indicated a substantial decline of juvenile eels migrating upstream in the Sud-Ouest River (lower St. Lawrence River) between 1999 and 2005. Trends in some areas (New Brunswick) were mixed while other areas (Newfoundland, southwest Nova Scotia) indicated some declines between the 1980 and the 2000s.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

The American Eel was assessed as Special Concern by COSEWIC in April 2006. The status was re-examined by COSEWIC in May 2012 and designated Threatened. It currently has no status under the federal Species at Risk Act. In Ontario, the American Eel was listed as Endangered and became protected under the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007. In Québec, the American Eel is ranked as vulnerable. In Newfoundland and Labrador, it has been listed under the provincial listing (ESA) as vulnerable. The American Eel has been ranked as secure in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, apparently secure-secure in Prince Edward Island, apparently secure in Canada and globally by NatureServe (as of 2006).

Inside the secret, million-dollar world of baby eel trafficking

Richard Cuthbertson · CBC News · Posted: Jun 25, 2019 Pertains to NS