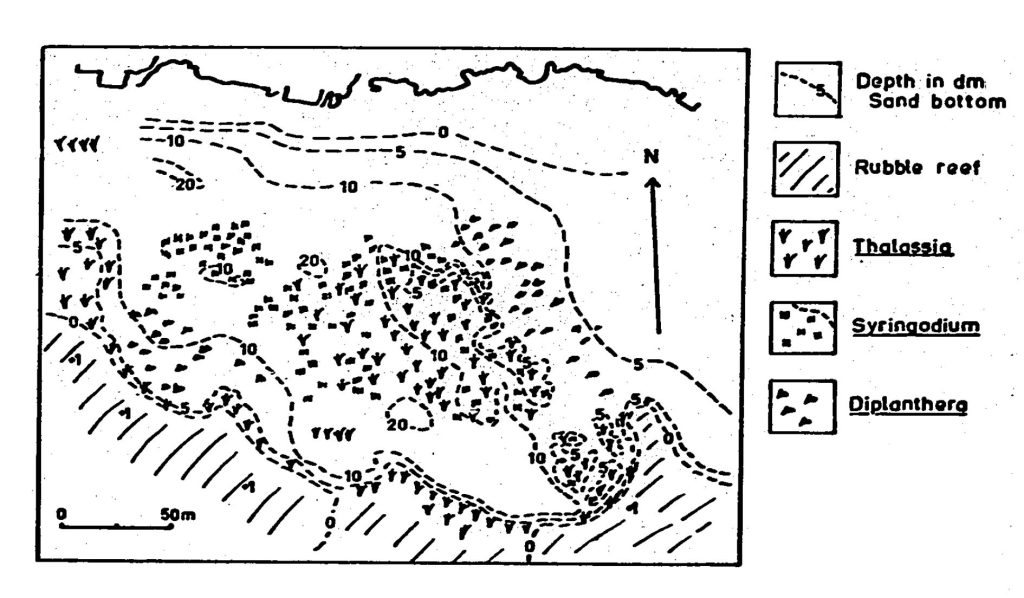

Source: Mostly to-date unpublished observations on Barbados seagrass beds by D. Patriquin in 1968/9; and by D. Patriquin with collaboration of R. Scheibling, L. Vermeer in 1994; and draft manuscripts by D. Patriquin. View ObsSG for details.

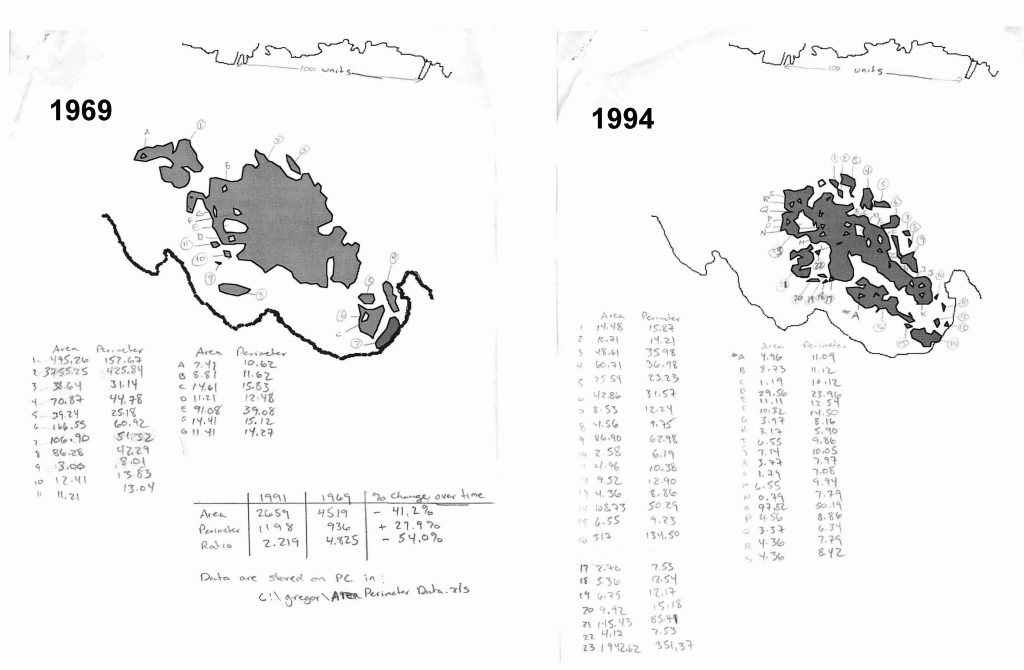

Fig SL-4. Map of seagrass area at St. Lawrence in 1969 and 1994. Pencilled in are calculations of the total area(s) and total length of the perimeter(s). Between 1969 and 1994, the total area decreased and the beds became more fragmented, resulting in a 54% decrease in the ratio of area to perimeter; there was more fargmentation and edge in 1994, increasing susceptibility to erosion.

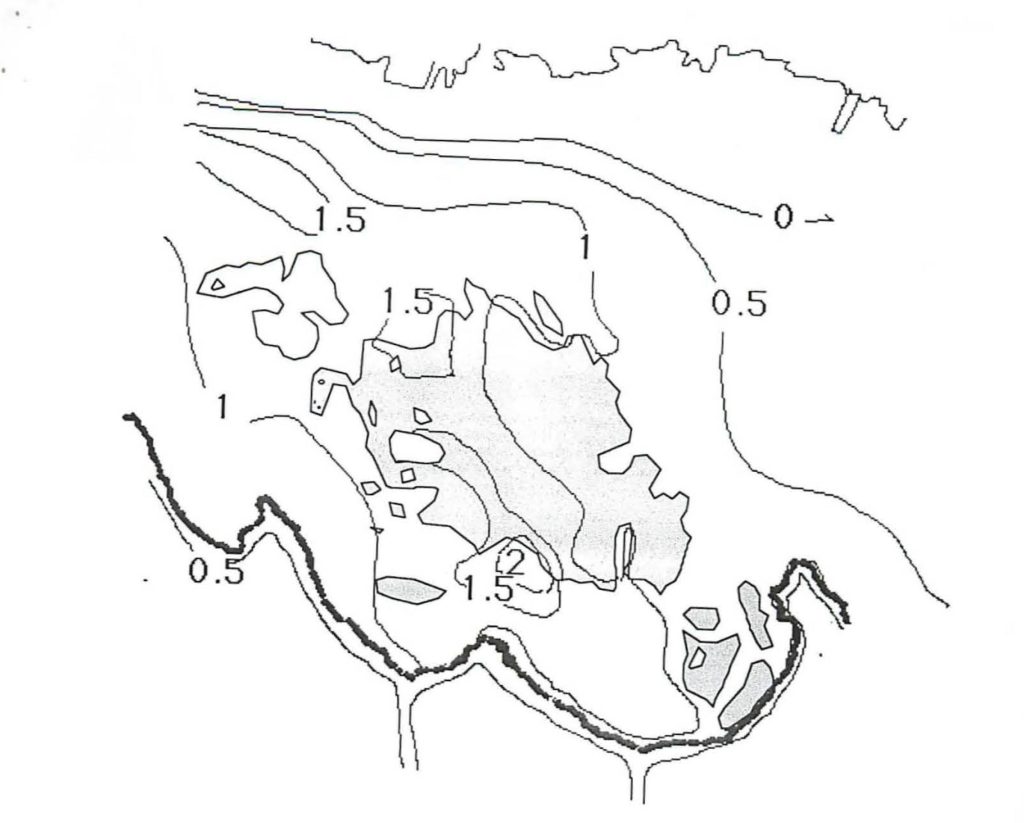

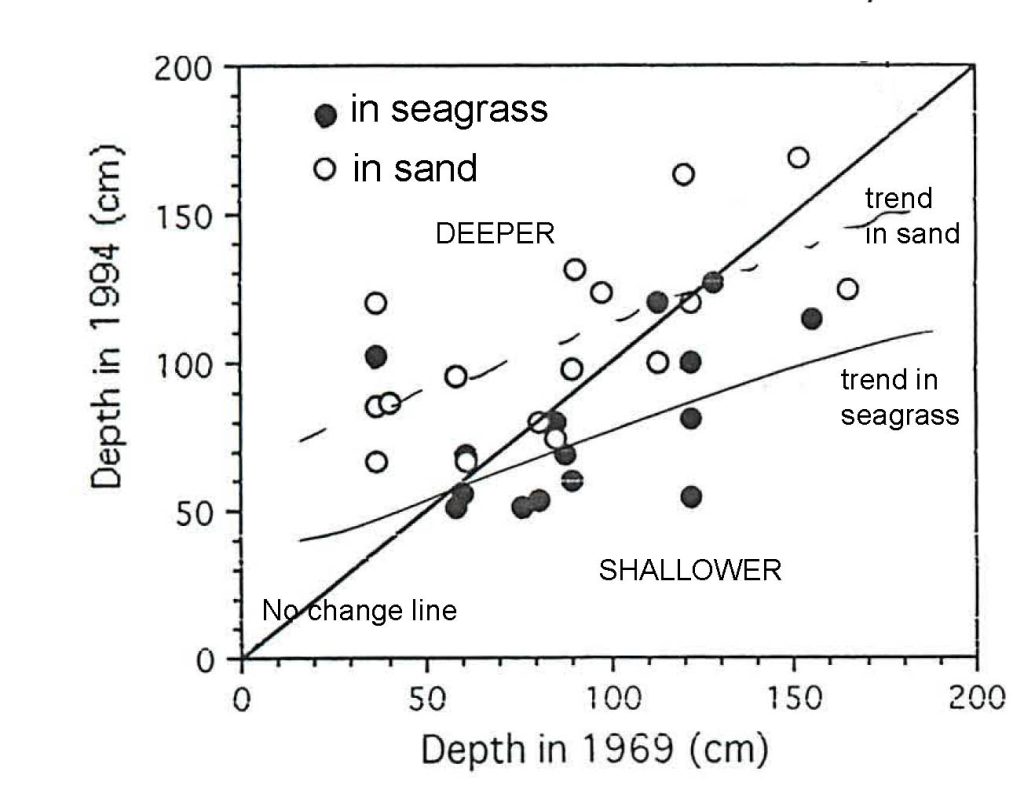

Fig SL-5. Depth at individual Stations measured in 1969 and 1994. In 1969, all stations were within seagrass bed. In 1994 some stations were now sand, some still seagrass. As could be expected, sites in 1994 without seagrass were in general deeper than they were in 1969. Not necessarily expected, there was a trend for Stations that retained seagrass to be shallower, i,e,.they accumulated and stabilized some of the sand that had been eroded; scarps within seagrass beds and edges if the bed(s) had noticeably much higher relief in 1994 compared to 1969 (data not shown here). Trend lines are eye-balled.

SL Tables XI and XII in a text readable PDF: SLtableXI&XII

SL Tables XI and XII in a text readable PDF: SLtableXI&XII

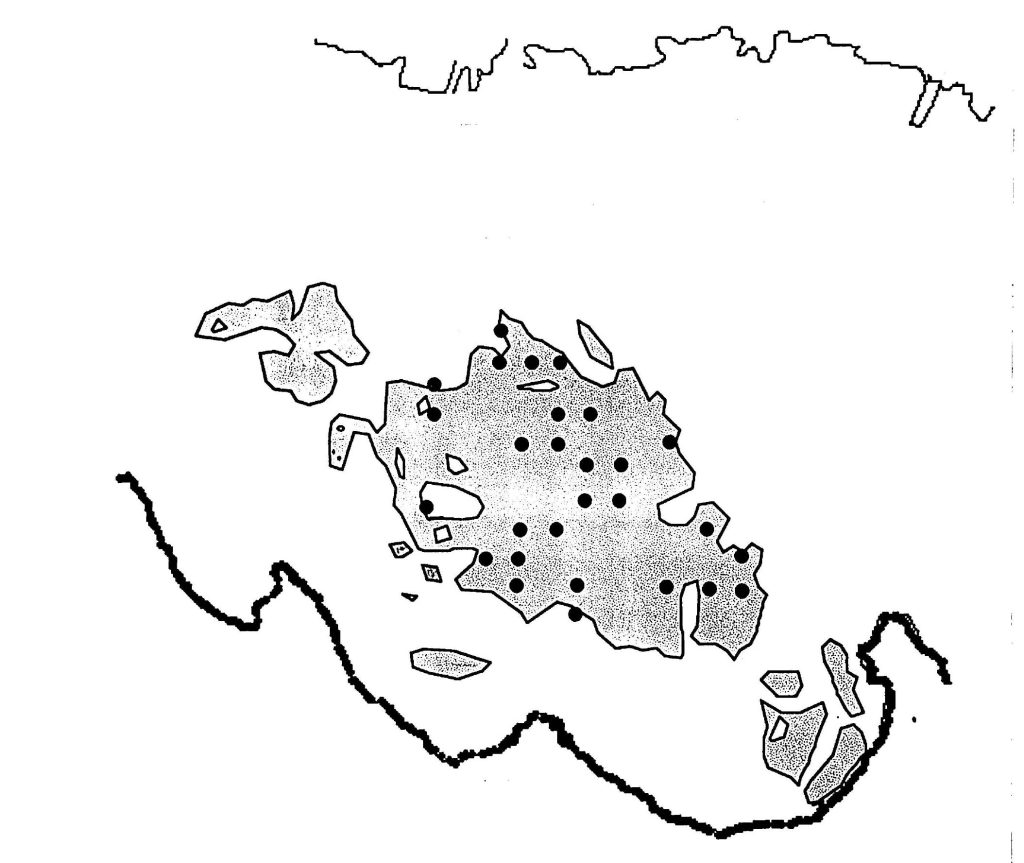

Results (Source: DP Draft manuscript, 1999).

- Data from aerial photography and ground truthing indicated the seagrass bed area in 1994 was 57% of the area 1969 (SL Table X1). The seagrass bed(s) also became more fragmented (Fig SL-4) and the perimeter-to-area ratio of 1969 increased by a factor of 2.25 in 1994 (SL Table XI).

- In 1994, seagrass was present at 23 of the 27 stations sampled in 1969: all 27 stations were within seagrass area in 1969.

- The fresh weight of T. testudinum in 1994 for quadrats in which there was seagrass was 50% of that in 1969, while fresh weight of S. filiforme was 1.8 fold that in 1969 and there was very little change in total seagrass fresh weight (SL Table X2. T. testudinum Maximum Leaf Length (Lm) was reduced significantly, but not by a large factor; leaf width was not reduced significantly in 1994 compared to 1969 (SL Table II).

-

The quadrat data demonstrate complete loss of S. radians and P. furcata from the St Lawrence bed where these species were common in 1969.

- In 1994, bottom depth was significantly greater than in 1969 at sites where seagrass had been present in 1969 but was not present in 1994, while it was significantly less (shallower) where seagrass was present in both years. This suggests that much of the sand that became mobilized by erosion of seagrass bed, subsequently became trapped in seagrass remaining.

- An overgrazing event was observed at this bed in 1969 after the survey was conducted. In September, large aggregations of sea urchins moved onto the bed from its seawardface, apparently originating seaward of the rubble bank (Fig). They were clustered one on top of the other and initially moved across the bed in one large aggregation with a distinct front. As the canopy was destroyed, wave action increased and urchins were washed further into the bed by wave action. Lilly (1975) studied growth of sea urchins during the event.He noted that “growth was rapid until November, 1969, when signs of overgrazing were first seen. By December all Thalassia blades were reduced to stubble…In March, the urchins appeared to be less numerous and the Thalassia blades were somewhat longer.” When D.P. last observed the bed, in February 1970, counts in 8 one-quarter m2 quadrats indicated an average of 4.5 seaurchins per m2 and the adjacent beach areas were littered with sea.urchins tests. The canopy cover had been completely removed, and the bottom had wave ripples similar to those in completely grass free area (photo). A small reef-like mound dominated by Porites porites and sponges at the seaward face of the bed had been complete dispersed.We did not observe outbreak of sea urchins in 1994, however in Brigitta I. van Tussenbroek et al., 2014, co-author HA Oxenford apparently provided info on occurrence “a population explosion sea urchins” in the monitoring interval (04/1993 to 09/2001):

At six stations the seagrass beds collapsed: in Bermuda (3 stations) the decline was due to excessive grazing by sea turtles; in Barbados (2 stations) poor water quality followed by a population explosion of sea urchins and subsequent storms were responsible.

Discussion of changes 1969-94 (Source: DP Draft manuscript, 1999).

The St. Lawrence bed underwent marked change between 1969 and 1994, fragmenting greatly, shallowing in the seagrass colonized areas; in seagrass-colonized areas, the proportion of S. filiforme increased markedly, but there was no reduction in fresh weight of seagrasses per unit area. There are several factors that may have contributed to and acted to maintain this change:

— Overgrazing of the seagrass bed by sea urchins: The 1969/70 event was similar to one described by Camp et al., 1973. Outbreaks of this intensity have not been reported for Barbados subsequently. Recovery was not subsequently monitored, however diagrams of marine vegetation cover taken from aerial photographs in 1973 indicate very sparse growth of seagrasses in the area of the study bed in contrast to comparison that author made with 1950 (XXX., 19XX). Sea urchins can keep patches within seagrass beds free of seagrass if high densities (>20m-2 for Lytechinus variegatus) are maintained (Valentine and Heck, 1991). However, this could not be a mechanism for maintenance of reduced area at St. Lawrence as sea urchins are harvested as delicacy in Barbados, and such densities were certainly not retained; few were observed in 1994.

— On the loss of corals

The status of the coral populations in the seagrass beds provides another indicator of the stability of the seagrass environment between 1969 and 1994. The two species observed at at St. Lawrence, Siderastera radians and Porites furcata (also observed at Bath, and at Carriacou where Manicina areolata is also common i seagrass beds) are or were once common in shallow, T. testudinum-colonized reef flat and shallow subtidal environments (Squires, 1958; Margalef, 1962; Kissling 1965, Glynn, 1973 Goreau, 1959). They are adapted in different ways to these environments of regular wave action, high suspended sediment loads, and moving substrata, where firmly attached types would be quickly smothered. Common features of mobile species are relatively short lifespans,brooding of larvae and relatively high tolerance of suspended sediment or burial (Gill and Coates, 1977; Rice and Hooter, 1992).

Siderastrea radians is most common as a flattened or hemispherical colonies firmly attached to hard substrates; the free-living, spherical fonns (corralliths: Glynn, 1973) are typically found in T. testudinum-colonized rubble substrates in the reef flat zone where they are regularly overturned. Lewis(1987) described the growth and mortality patternsof S.radians on the east and south coasts of Barbados, including a population from the Bath seagrass bed and a bed nearby the StLawrence bed of this study The colonies develop on a dead coral branch or other hard fragment, initially confonforming to the shape of the fragment; as they grow larger, colonies tend to become more rounded and grow over the entire fragment, finally having no externally visible attachment; in areas of mobile substrates, there is reduced mortality amongst those forms with greater sphericity. The largest individual (7.2 em wide) was 4 years old. It exhibits little, if any growth from fragments. As it is not, apparently, genetically distinct from the more common forms on hard surfaces, recruitment of populations to seagrass beds should not be dependent on the seagrass bed populations alone.

Porites porites f. furcata is a delicately branching coral that forms colonies consisting of grey- yellow, mostly dichotomous branches (Littler et at, 1989). Genetic and morphological analysis supports specific distinctiveness of this form (Wells, 1992) thus here it is referred to as P. furcata. Unlike the other S.radians and M.areolata, it fragments quite readily, and this is an important means of maintaining populations(Highsmith 1982). Most specimens in seagrass beds are found unattached (Kissling, 1965 ); boring sponges can effect weak attachment (Highsmith, 1982). Seagrass vegetation appears to help stabilize the colonies (Kissling, 1965). Various attitudes of the coral through its ontogeny are revealed by the condition of the branches,as the older parts are more heavily encrusted (Squires, 1958). Large patches are sometimes found in deeper water (3-10m;Highsmith,1982). Experimental studies byLittler et ale(1989)in a Belize reef flat indicate that P. furcata is relatively palatable to herbivorous fish, and that Its seaward abundance in reef flat environments is limited by predation – three dimensional reef structures but not the reef flats areas provide protection to herbivorous fish from carnivores, and grazing by the herbivorous close to the reef limit the coral’s occurrence there. They were not certain to what extent wave action might also limit colonization of hard surfaces subject to heavy wave action. At Bath, P. furcata occurs as a free-living form in the seagrass beds; it also occurs in abundance in a very flattened, firmly attached form on wave swept hard pavement type bottom with little relief seaward of the seagrass beds; that area also supports vigorous growth of fleshy algae such as Dictyota, Sargassum, and Wrangelia spp, which suggests that herbivory is very limited. (In contrast, large fleshy algae are not found in the equally wave intense areas within the cavernous platfonn area). Hence at Bath, the populations seaward of the seagrass bed probably contribute to recruitment in the seagrass bed both though larvae and fragments. Such sources would not be available at St Lawrence, and for most sites at Carriacou.

The complete loss of corals at St Lawrence 1969-1994 me be attributable to the high degree of fragmentation of the bed(s) which would increase the probability of the corals being swept sandy areas where they do not survive; increased sand transport in this area may also have been involved.

— Increased transport of sand into the area. Construction of groins along this coast have increased the amount of sand. The depth data suggest that seagrass colonized areas were significantly shallower in 1994 than in 1969, and this was obvious to the senior author. Increased sediment transport into the area could be factor favoring S. filiforme over T. testudinum because of its above ground rhizomes and high growth rates of vertical shoots (ref); amongst 6 Philippine species. Thalassia hemprichii is most readily displaced by sediment burial (Duarte et al., 1997). However it seems unlikely that it would generate more áfragmentation of the bed. Lugo-Fernandez et al. (1994) reported that photographs taken 2 years before and 4 years after a severe hurricane on Mararita reef (Puerto Rico) indicate a elimination of Thalassia-Syringodium beds in an area where energy is most concentrated, but a corresponding increase in size in central and western areas where deposition of sediment would be expected. Sediment deposition seems to be most detrimental when it is episodic in nature and smothers beds for more than several months (Shepard et al., 1989; Duarte et al., 1997) or has a high content of silt and clay (Terrados et al., 1998). However, shallowing as at St. Lawrence could effect patch formation by bringing S. filiforme closed to exposing it to greater intensity of disturbance by waves, increasing the probability of disruption and formation of blowouts.

— Increased boating and foot traffic: the area has become very popular for snorkelling, and in 1994, people were observed walking over the beds at low water with boats in tow, sometimes mooring them temporarily in the beds. Such activity is well known to disrupt seagrass bed integrity.

These physical factors would seem sufficient to explain the changed state of the St. Lawrence bed. however, as at Bath, there have been other changes in the environment in the interim and these could have contributed to the changes in the seagrass bed. Nutrient loading at St. Lawrence increased between 1969 and 1994 (2.9 mg L-1 in 1997, 8.4 mg L-1 in 1992: Delan, 1995), and although not measured, growth of non-calcareous epiphtes was fairly heavy on the older parts of leaves of both T. Testudinum and S. filiforme in 1994, while it has not been noted as such in 1969. It is possible also that other contaminants in the marine environment caused more stress to the seagrasses in 1994 than in 1969.

On sep. pages: Survey Methods, References.

Note: Lotus Vermeer in her PhD thesis* made use of the 1969 and 1994 observations and offers some detailed interpretation of them and insights into what drove significant changes between 1969 and 1994.

*Lotus Vermeer, 2000. Changes in seagrass growth and abundance of seagrasses in Barbados, West Indies, PhD thesis, Dalhousie University. See Ch 5.