DRAFTING…

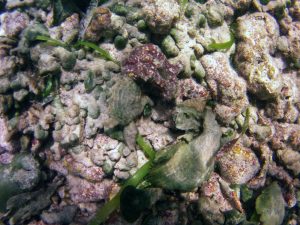

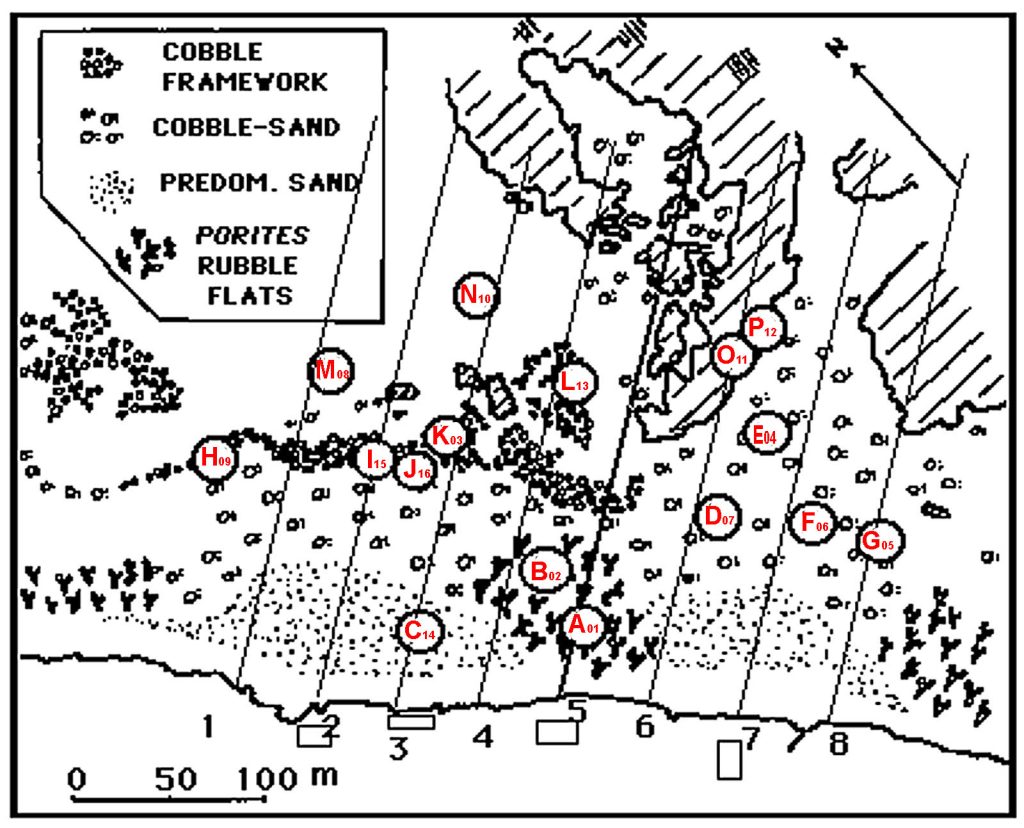

Pic I. Algal Ball (Rhodolith) at Bath Feb 23, 2015. Reported on iNaturalist . Location is just seaward of seagrass bed on Transect 3, between Stns K and N (Fig. 1 below) Click on images for larger versions.

Early on in my studies of seagrass beds at Bath on the east, windward coast of Barbados 1967-1979, I encountered and was fascinated by what I called “Algal Balls”, golf-ball to baseball (softball) size spherical structures with a bumpy surface.

They were pink to reddish color, which I recognized as coralline algae; when I broke them apart on shore using a hammer and chisel, there was always a core of a coral fragment with the coralline algae in layers around it.

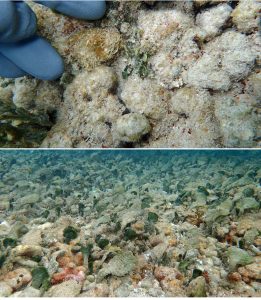

Clusters of these algal balls occurred in depressions on hard surface (formed largely by coralline algae) seaward of the seagrass beds in an area subject to constant heavy wave action. I speculated that the spherical shape was due to regular disturbance and movement of the algal balls by the wave action.

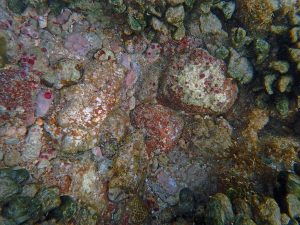

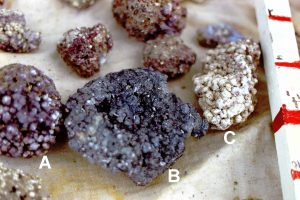

PicII Rhodoliths collected at Bath, 1969 A: typical rhodolite from location seaward of seagrass beds, B. Blackened rhodolite, ‘likely had been buried in Thalassia bed and stained by iron sulphides, subsequently released by erosion. C: “White” rhodolith, typical of buried rhodoliths exposed at seagrass scarps,

Masses of algal balls washed into shallower areas where they formed part of the Cobble Framework substrates in the seagrass beds; once covered they die and often become blackened (Spec B at left) due to the anoxic, sulphidic conditions of substrataes colonized by the seagrass Thalassia testudinum.

In 1968 I was one of about a dozen attendees of a 6-week “Advanced Science Seminar on Organism-Sediment Interrelationships” held at the Bermuda Biological Station. The seminar, which involved a combination of seminars/classroom time and field studies, was organized and directed by Ralph Ginsburg, a carbonate geologist well known for his research on coral reefs current and ancient. One of the participants in the seminar was geologist Alfonso Bosselini who had a particular interest in following up a reported occurrence in 1967 of “algal nodules” in shallow water at Whalebone Bay on St. George Island; such nodules were well known in the geological record, but known living algal nodules were largely restricted to deeper sites beyond SCUBA range, and consequently “very little is known of their local environments and almost nothing about their growth”.*

I remember visiting Whalebone Bay and how the topography, wave action and communities – including aggregations of algal balls (red algal nodules to the geologists) were similar in many ways to what I had viewed Bath. Boselini and Ginsburg subsequently published a seminal paper* on their studies at Whalebone Bay, giving the name “Rhodolites” to the living, unnattached, red algal “nodules”; subsequent authors have mostly used the term “Rhodolith” (meaning “Red Rock”) in its place **so that is the term I am using.

*Form and internal structure of recent algal nodules (Rhodolites) from Bermuda Bosellini, A.; Ginsburg, R.N. 1971 in Journal of Geology; see Abstract below.

*The occurrence and ecology of recent rhodoliths—a reviewDaniel W. J. Bosence in Coated Grains Conference Proceedings, Springer, pp Pages 225-242

Boselini and Ginsburg describe two growth forms of rhodolites at Whalebone Bay, laminar and columnar:

The growing rhodolites of Whalebone Bay are pebble to cobble-sized spheroids found at depths of 1-2 m. In section, a nucleus (either algal or foreign) is surrounded by a laminated shell or coralline algae with two different growth forms: laminar and columnar. In almost all the larger rhodolites the nucleus is invariably succeeded first by laminar and then columnar structure. Growing spheroidal and ellipsoidal rhodolites with smooth surfaces (laminar structure) are concentrated in sandy channels; those flattened ones with bumpy surfaces (columnar structure) are half buried in skeletal sand or trapped in rock-floor depressions. Evidently, the spheroidal form and laminar structure indicate frequent movement, while the flattened form and columnar structure indicate immobility.

Both growth forms were present at Bath, concentrated as described under particular conditions as described for Whalebone Bay.

I took samples of the Bath rhodoliths and other coralline algal specimens back to Canada when I returned there in 1970. Subsequently I spent part of a postdoc working with Phycologist R.K.S. Lee at the Botany Division of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Ottawa. There I learned the specialized techniques required to identify coralline algae, and was able put a name for the coralline algae on those Bath rhodoliths: Lithothmnion syntrophicum Foslie 1901. In 1970, that was renamed as Mesophyllum syntrophicum(Foslie) W.H.Adey 1970. The type locality: Harrington Sound, Bermuda! So it’s likely that at least some of the coralline algae forming the shallow water Bermuda rhodolites and at least some of those at Bath are the same species.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

– Form and internal structure of recent algal nodules (Rhodolites) from Bermuda.

Bosellini, A.; Ginsburg, R.N. 1971 in Journal of Geology Full article available as PDF

Abstract

The growth forms and internal structure of living coralline algal nodules (here termed rhodolites) from a shallow Bermuda bay contain a surprisingly sensitive record of the frequency of their movement by wave action. The growing rhodolites of Whalebone Bay are pebble to cobble-sized spheroids found at depths of 1-2 m. In section, a nucleus (either algal or foreign) is surrounded by a laminated shell or coralline algae with two different growth forms: laminar and columnar. In almost all the larger rhodolites the nucleus is invariably succeeded first by laminar and then columnar structure. Growing spheroidal and ellipsoidal rhodolites with smooth surfaces (laminar structure) are concentrated in sandy channels; those flattened ones with bumpy surfaces (columnar structure) are half buried in skeletal sand or trapped in rock-floor depressions. Evidently, the spheroidal form and laminar structure indicate frequent movement, while the flattened form and columnar structure indicate immobility. The frequency of movement recorded by the laminar structure was determined by observation of marked rhodolites. Specimens of 80 mm were moved 3 m in the sandy channels by waves generated by winds of 15 knots. Winds of 15 knots or more occur monthly throughout the year and much more frequently during the fall and winter. The relationships between form and internal structure and frequency of movement observed in these shallow-water rhodolites may also prove to be useful for interpreting the growth conditions of other Recent rhodolites from deeper water, 10-100 m, as well as those of fossil rhodolites.

– An Overview of Rhodoliths: Ecological Importance and Conservation Emergency

Dimítri de Araújo Costa et al., 2023 in Life (Basel)Abstract

Red calcareous algae create bio-aggregations ecosystems constituted by carbonate calcium, with two main morphotypes: geniculate and non-geniculate structures (rhodoliths may form bio-encrustations on hard substrata or unattached nodules). This study presents a bibliographic review of the order Corallinales (specifically, rhodoliths), highlighting on morphology, ecology, diversity, related organisms, major anthropogenic influences on climate change and current conservation initiatives. These habitats are often widespread geographically and bathymetrically, occurring in the photic zone from the intertidal area to depths of 270 m. Due to its diverse morphology, this group offers a special biogenic environment that is favourable to epiphyte algae and a number of marine invertebrates. They also include holobiont microbiota made up of tiny eukaryotes, bacteria and viruses. The morphology of red calcareous algae and outside environmental conditions are thought to be the key forces regulating faunistic communities in algae reefs. The impacts of climate change, particularly those related to acidification, might substantially jeopardise the survival of the Corallinales. Despite the significance of these ecosystems, there are a number of anthropogenic stresses on them. Since there have been few attempts to conserve them, programs aimed at their conservation and management need to closely monitor their habitats, research the communities they are linked with and assess the effects they have on the environment.