Extracts from:

The transformation of Caribbean coral communities since humans

Katie L. Cramer et al., 2021 in Ecology & Evolution

TABLE 1. Coral life-history groups and their defining traits.

Abstract

Abstract

The mass die-off of Caribbean corals has transformed many of this region’s reefs

to macroalgal-dominated habitats since systematic monitoring began in the 1970s.

Although attributed to a combination of local and global human stressors, the lack

of long-term data on Caribbean reef coral communities has prevented a clear under-

standing of the causes and consequences of coral declines. We integrated paleo-

ecological, historical, and modern survey data to track the occurrence of major coral

species and life-history groups throughout the Caribbean from the prehuman period

to the present. The regional loss of Acropora corals beginning by the 1960s from local

human disturbances resulted in increases in the occurrence of formerly subdomi-

nant stress-tolerant and weedy scleractinian corals and the competitive hydrozoan

Millepora beginning in the 1970s and 1980s. These transformations have resulted in

the homogenization of coral communities within individual countries. However, in-

creases in stress-tolerant and weedy corals have slowed or reversed since the 1980s

and 1990s in tandem with intensified coral bleaching and disease. These patterns re-

veal the long history of increasingly stressful environmental conditions on Caribbean

reefs that began with widespread local human disturbances and have recently culmi-

nated in the combined effects of local and global change.

From the text

… This configuration [of life history groups] roughly follows Grime’s arrangement of plant species into three basic life-history strategies: competitive species that maximize growth, stress-tolerant species that maximize survival, and ruderal or weedy species that maximize fecundity (Grime, 1977, 2006). A fourth category, generalist species, represents a mixture of these strategies. However, because the generalist group was composed primarily of corals that are less common in the Caribbean and their presence and absence was not consistently noted in our dataset, this group was not included in our analyses.

Graphical Abstract

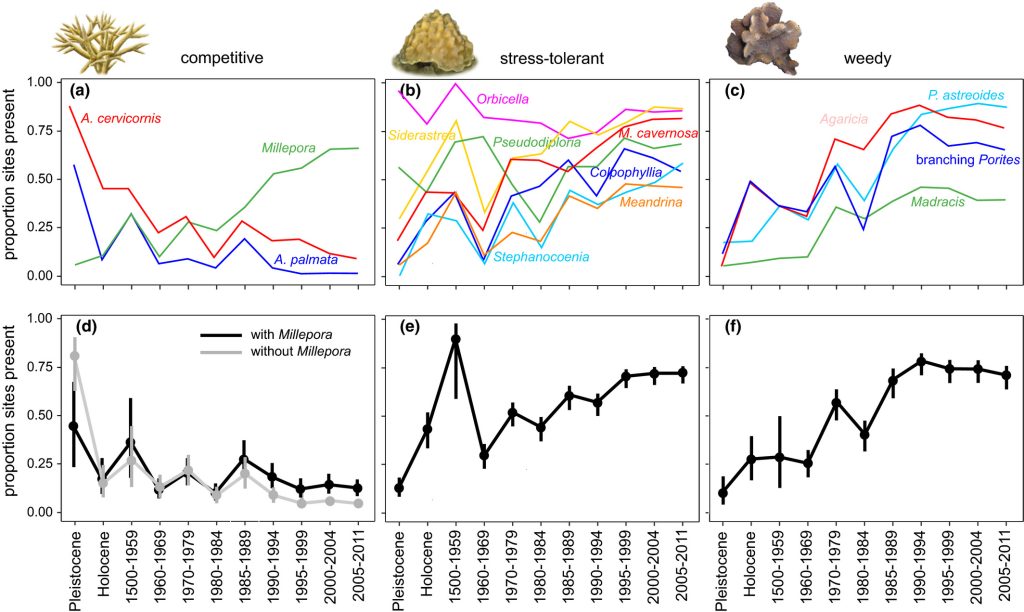

We integrated paleoecological, historical, and modern survey data to track the prevalence of major coral species and life-history groups throughout the Caribbean from the prehuman period to present. This extended time series reveals that Caribbean coral communities have been transformed via three distinct stages since humans: (a) declines in competitive corals by the 1960s, (b) increases in stress-tolerant and weedy corals occurring by the 1970s and 1980s, and (c) declines or leveling-off of stress-tolerant and weedy corals since the 1980s or 1990s. These patterns reveal the long history of increasingly stressful environmental conditions on Caribbean reefs that began with widespread local human disturbances and have recently culminated in the combined effects of local and global change.

1 INTRODUCTION

Living cover of reef-building corals has declined on Caribbean reefs by 50% to 80% since systematic monitoring began in the late 1970s (Gardner et al., 2003; Jackson et al., 2014) with many reefs altered from coral- to algal-dominated habitats (Hughes et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2014). Coral declines have been attributed to multiple anthropogenic stressors including fishing, land-based sedimentation and pollution from agriculture and coastal development, and global warming as well as epizootics afflicting corals and urchins (Aronson & Precht, 2001; Hughes et al., 2007; Jackson et al., 2014). The mass mortality of the long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum in the early 1980s removed the last abundant herbivore from reefs that were largely devoid of herbivorous fish after decades to centuries of overfishing (Jackson, 1997; Jackson et al., 2001; Lessios, Cubit, et al., 1984; Lessios, Robertson, et al., 1984; Pandolfi et al., 2003), precipitating an explosion of macroalgae on reefs across the Caribbean (Jackson et al., 2014). Outbreaks of White Band Disease appeared on many reefs around this same time, eventually killing over 80% of the remaining elkhorn coral Acropora palmata which previously dominated reef crest zones and staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis which previously dominated midslope zones (Bruckner, 2002; Bythell et al., 2004; Gladfelter, 1982). These events were followed by regional coral bleaching in the 1990s, leading to further increases in coral diseases and in some instances a further replacement of corals by macroalgae (Eakin et al., 2010). These factors acted synergistically to rapidly transform coral communities. A recent Caribbean-wide analysis of Acropora presence and dominance from the prehuman period to the present revealed that the loss of these corals initially began in the 1950s and 1960s, decades before the first recorded observations of coral disease and bleaching (Cramer, Jackson et al., 2020). These changes are historically unprecedented—paleoecological studies show that modern Caribbean coral community composition, devoid of major framework building corals Acropora and Orbicella (Jackson et al., 2014), is unlike anything in the previous 220,000 years (Jackson, 1992; Mesolella, 1967; Pandolfi & Jackson, 2006).

While the long-term decline of acroporid corals has been documented across the Caribbean, long-term regional trends in the full reef coral community have not been assessed. Although isolated surveys of altered reefs have found an increase in the relative abundance of low relief “weedy” species such as Porites and Agaricia over the past few decades (Aronson et al., 2004, 2005; Cramer et al., 2012; Green et al., 2008), the magnitude and geographic extent of community change are unresolved. Reconstructing long-term change in the full reef-building coral community will shed light on the anthropogenic causes and ecological consequences of recent coral declines and can help guide management interventions by providing accurate baseline data from which to set appropriate recovery targets. We compiled an extensive dataset on the occurrence of common hermatypic coral species and genera at thousands of individual reef sites across the Caribbean spanning the Late Pleistocene epoch (~131,000 ybp)—when humans were absent from the Americas (Cooke, 2005)—up to 2011. By pinpointing the initial timing of major community transformations, we inferred general anthropogenic causes of change (i.e., local human stressors and/or climate change). To provide additional insight into the ecological context of change, we also tracked change in (a) major coral ecological guilds based on several life-history traits and (b) inter-site community heterogeneity.