DRAFTING…

| From Lotus Vermeer, 2000. Changes in seagrass growth and abundance of seagrasses in Barbados, West Indies, PhD thesis, Dalhousie University.

Ch 3: EFFECTS OF SHORT-TERM CHANGES NI COASTAL WATER QUALITY ON SEAGRASS ABUNDANCE AND LEAF GROWTH IN BARBADOS Ch 5: CHANGES IN ABUNDANCE AND LEAF GROWTH OF SEAGRASSES NI THE EASTERN CARIBBEAN: 1969-1994 |

| From Caribbean-Wide, Long-Term Study of Seagrass Beds Reveals Local Variations, Shifts in Community Structure and Occasional Collapse Brigitta A van Tussenbroek et al., 2014 in Plos 1

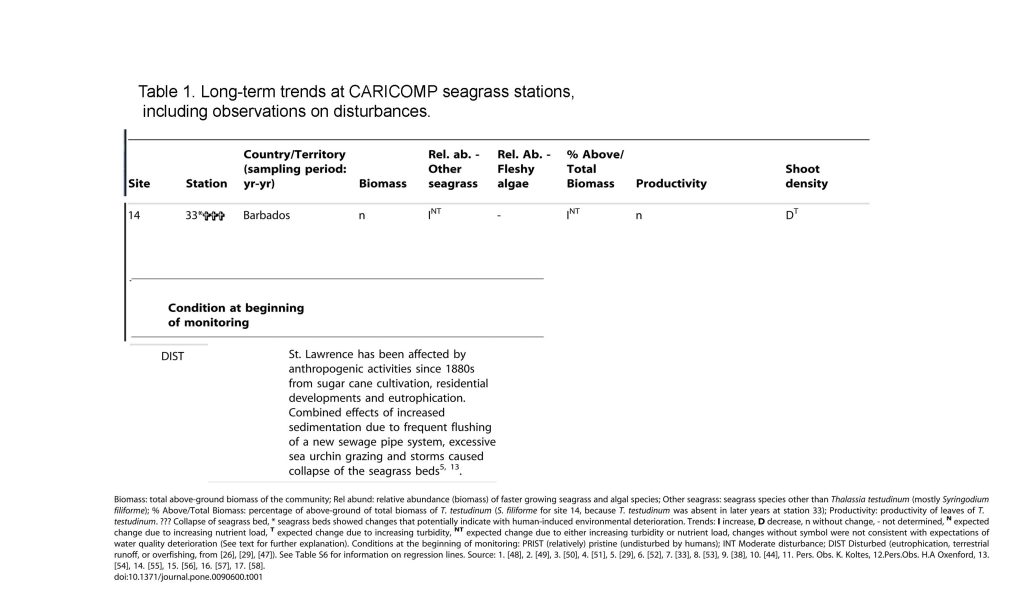

This study presents the results of a long-term (1993–2007, with some continuing to the present) Caribbean-wide seagrass monitoring initiative: the Caribbean Coastal Marine Productivity (CARICOMP) program….The CARICOMP program has generated a Caribbean-wide dataset using a simple, low-cost but standardized sampling protocol, consistent among sites over time…The seagrass communities at the majority (25) of the 35 stations included in the analysis for longer-term trends in the community showed changes in at least one of the six selected parameters (Table 1, Table S6). At six stations the seagrass beds collapsed: in Bermuda (3 stations) the decline was due to excessive grazing by sea turtles; in Barbados (2 stations) poor water quality followed by a population explosion of sea urchins and subsequent storms were responsible; and in Mexico, a coastal bed (1 station) was buried by sediments during a hurricane. Most monitoring stations (46 out of 52) were exposed at least once to a major meteorological event (hurricane or tropical storm, Table S1) during the study period, but apart from the above-mentioned collapse of communities in Mexico and Barbados (where the storms were not the main cause of collapse), minor impacts of storms were registered only at Belize-station 26 and Venezuela-stations 47 and 48 (Table 1). At 15 (43%) out of 35 studied stations (Table 1, Fig. 5), changes in the seagrass beds were consistent with hypothesized change scenarios of increased turbidity (Site 4-Stations 8 & 9 and Site 21-Station 49) or increased nutrient input (Site 2-Station 5; Site 5-Stations 10 thru13; Site 8-Station17; Site 10-Station 21; Site 12-Station 25; Site 14-Stations 33 & 34 Site 20-Stations 47 & 48). Most stations that showed shifts in community structure consistent with environmental degradation were reported to have received little or only moderate human-induced impacts at the onset of the study (Fig. 6). …The fate of the seagrass beds at Barbados-St. Lawrence lagoon (site 14) is a good example of how long-term (chronic) anthropogenic stress can act synergistically with acute extreme disturbance events [over-grazing by an exceptionally strong recruitment of sea urchins, Hurricane Ivan (2004) and Tropical Storm Emily (2005)] to cause collapse of an ecosystem. Even after 7 years, this lagoon has shown only minimal recovery, with just a few impoverished T. testudinum plants in areas of coral rubble and a very sparse vegetation of Halodule wrightii appearing in the sand areas (H. Oxenford, unpublished data). |