From A NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN FOR BARBADOS (2002)

“Seagrass areas, commonly known as seagrass beds or meadows, are distributed along the coast in shallow water where sunlight penetration is adequate to facilitate photosynthesis. Delcan

(1994b), reported seagrass beds along the west coast at Shermans, Six Men’s Bay, Speightstown and Brighton; along the southwest coast at Bridgetown, Hastings, Rockley, Worthing, St.Lawrence, Dover, Maxwell, Welches, Oistins, Enterprise and Atlantic Shores of Barbados; and along the east coast at Bath and Conset Bay.“There is evidence that the quality of the local coastal marine water is deteriorating due to increased sedimentation, eutrophication and sewage pathogens, localised increases in

temperature, decreases in salinity, and perhaps increases in toxins (Delcan, 1994a). There is also evidence to suggest that grazing by fish and sea urchins is an important mechanism for recycling nutrients within the beds. Heavy fishing pressure that results in the removal of these animals can therefore also negatively affect the vibrancy seagrass beds. Physical damage in coupled with poor water quality will negatively impact on the vibrancy of seagrass beds. It is therefore probable that the local seagrasses are being impacted negatively by many coastal activities and land based sources of pollution and urgent attention must be given to ways of minimizing these impacts”

Caribbean-Wide, Long-Term Study of Seagrass Beds Reveals Local Variations, Shifts in Community Structure and Occasional Collapse

Brigitta I. van Tussenbroek et al., 2014 PLOS ONE 9(5): e98377 Abstract

The CARICOMP monitoring network gathered standardized data from 52 seagrass sampling stations at 22 sites (mostly Thalassia testudinum-dominated beds in reef systems) across the Wider Caribbean twice a year over the period 1993 to 2007 (and in some cases up to 2012). Wide variations in community total biomass (285 to >2000 g dry m−2) and annual foliar productivity of the dominant seagrass T. testudinum (<200 and >2000 g dry m−2) were found among sites. Solar-cycle related intra-annual variations in T. testudinum leaf productivity were detected at latitudes > 16°N. Hurricanes had little to no long-term effects on these well-developed seagrass communities, except for 1 station, where the vegetation was lost by burial below ∼1 m sand. At two sites (5 stations), the seagrass beds collapsed due to excessive grazing by turtles or sea-urchins (the latter in combination with human impact and storms). The low-cost methods of this regional-scale monitoring program were sufficient to detect long-term shifts in the communities, and fifteen (43%) out of 35 long-term monitoring stations (at 17 sites) showed trends in seagrass communities consistent with expected changes under environmental deterioration.

Leaf epifauna of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum

J. B. Lewis & C. E. Hollingworth. 1982 Marine Biology volume 71, pages 41–49

Variation in ecological parameters of Thalassia testudinum across the CARICOMP network

K Koltes et al., 1997. Proceedings of the International Coral Reef Symposium Volume 8 Pages 663-668

Effects of shoot age on leaf growth in the seagrass Thalassia testudinum in Barbados

LA Vermeer & Wayne Hunte 2008. Aquatic Biology 2(2):153-160

———————————-

PUBLICATIONS BY DGP RELATED TO CARIBBEAN SEAGRASSES

The origin of nitrogen and phosphorus for growth of the marine angiosperm Thalassia testudinum Konig.

Patriquin, D.G. 1971. PhD Thesis, Marine Sciences Centre, McGill University, 193 pp. (Available from McGill University) Appendix B includes a general description of seagrass beds in Barbados and Carriacou (Grenada) as observed 1967-1970.

The origin of nitrogen and phosphorus for growth of the marine angiosperm Thalassia testudinum

Patriquin, D.G. 1972. Marine Biology 15: 35-46.

Nitrogen fixation in the rhizosphere of marine angiosperms

Patriquin, D.G. and R. Knowles. 1972. Marine Biology 16: 49-58.

Carbonate mud production by epibionts on Thalassia: an estimate based on leaf growth rate data.

Patriquin, D.G. 1972. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology 42: 687-689

Estimation of growth rate, production and age of the marine angiosperm Thalassia testudinum König

David G Patriquin, 1973. Caribb J Sci 13: 111−123 Available on Dalspace

Effects of oxygen, mannitol, and ammonium concentrations on nitrogenase (CzH2) activity in a marine skeletal carbonate sand.

Patriquin, D. G., Knowles, R. (1975). Mar. Biol 32: 49-62

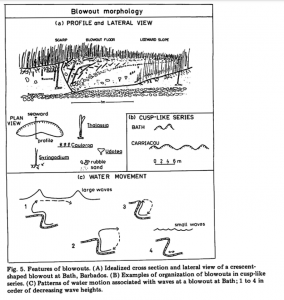

“Migration” of blowouts in seagrass beds at Barbados and Carriacou, West Indies, and its ecological and geological implications

“Migration” of blowouts in seagrass beds at Barbados and Carriacou, West Indies, and its ecological and geological implications

DG Patriquin, 1975 Aquatic Botany Volume 1, Pages 163-189. View PDF Abstract:

“Blowouts are grass-free depressions within seagrass beds at Barbados and Carriacou and reported in the literature to be common elsewhere in the Caribbean region. They are typically crescent-shaped in plan view with the convex side seaward, and are characteristic of elevated seagrass beds in regions of moderate to strong wave action. The seaward edge is steep and exposes rhizomes of Thalassia while the leeward edge slopes gently upward onto the seagrass plateau and is usually colonized by Syringodium. The general morphology of the blowouts, the zonation of organisms across them, and the existence at some blowouts of a lag deposit of cobble-sized material at the scarp base continuous with a rubble layer below the seagrass carpet suggested the blowouts “migrate” seaward. Measurements of erosion at the scarp and of advance of Syringodium onto the blowout floor over a period of one year confirmed this. It is estimated that in the region of blowouts any one point will be recurrently eroded and restabilized at intervals of the order of 5–15 years. Such processes limit successional development of the seagrass beds, disrupt sedimentary structures, and may result in deposits much coarser than those characteristic of the sandy seagrass carpet.”

The association of N2-fixing bacteria with sea urchins

Guerinot, M.L. and D.G. Patriquin. 1981. Marine Biology 62: 197-207.

Distribution and abundance of the invasive seagrass Halophila stipulacea and associated benthic macrofauna in Carriacou, Grenadines, Eastern Caribbean. Scheibling, Robert E., Patriquin, David G, and Filbee-Dexter, Karen. 2018. Aquatic Botany 144: 1-8

Shifts in biodiversity and physical structure of seagrass beds across five decades at Carriacou, Grenadines

D. Patriqun, R. Scheibling, K. Filbee-Dexter, In Press (2024)

Ongoing:

In 1969, I conducted quantitative surveys of seagrass beds in Barbados and Carriacou as part of my PhD research, but not reported in detail in my thesis. I repeated the surveys in 1994 with the collaboartion of my Dal colleague, Bob Scheibling and support from Dr. Wayne Hunter, Director of the Bellairs Reseach Institutue, Except for a 1975 paper on blowouts and use of some of the data by Lotus Vermeer in her PhD thesis (2000), the quantitative results of these surveys have not been published.

I repeated the surveys in Barbados in 2015, and in Carriaco in 2016 and 2019, again with the collaboration of my Dal colleague, Bob Scheibling, One paper coming out of the recent studies at Carriacou – on occurrence of the invasive seagrass Haophila stipulacea at Carriacou in 2016 – has been published. A second paper on the Carriacou data for 1969, 1994 and 2016/9 has been completed and is awaiting publication. I am working on a set of technical reports on the Barbados observations (1969, 1994, 2015).

Also view Observations: Bath