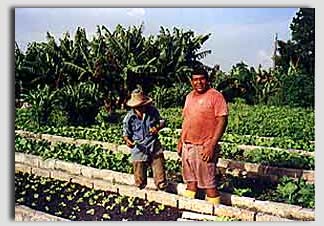

Organiponicos in Cienfuegos, Cuba

|

CONTENTS by Kristina Taboulchanas (2000) |

|

Overview

Prior to 1990 urban gardens were virtually non-existent in Cuba as they were perceived by many to be a sign of poverty and underdevelopment (Altieri et al.,1999). For years Cuba had been dependent on trade subsidies and imports from their Soviet allies. With the collapse of the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1989, Cuba was plunged into a serious economic crisis known as the Special Period. By 1990, Cuba had lost 85% of its imports including both agricultural inputs and food. Food imports had accounted for 57% of Cuban caloric intake (Murphy, 1999). Before the Special Period, Cuba's agriculture was based on an intensive monoculture approach that was heavily dependent on agrochemical imports. The demise of the USSR devastated Cuba's agriculture due to the loss of 80% of its fertiliser and pesticide imports (Warwick, 1999). The lack of agricultural imports forced Cuba to diversify farming practices and to adopt methods of organic agriculture. Most importantly, this crisis exposed Cuba's heavy dependency on imports and seriously threatened food security. The passing of the "Cuba Democracy Act" in 1992 and the "Helms-Burton Act" in 1996 (by the US Congress) exacerbated the economic crisis (Warwick, 1999). In response to this crisis the Cuban government launched a nation wide urban agriculture movement as an alternative source of food security.

Several different types of gardens have emerged in response to the Special Period including:

- Intensive gardens

These gardens are established in urban areas on uncontaminated, fertile soils that have access to an adequate water supply (Taboulchanas, MES 2001) - Popular Gardens

These gardens are located in vacant lots, old dumps and old parking lots in urban areas. They are managed and cultivated by community gardening organisations (Altieri et al., 1999). - Factory/Enterprise Gardens

These gardens are located on the land of state owned enterprises. In Cuba most workplaces offer free lunch to their workers. These gardens produce a proportion of the food to feed workers (Taboulchanas, MES 2001). - Household Gardens

These are small gardens located in people's front and backyards, rooftops or balconies. - Hydroponicos

These gardens are located in vacant lots in urban and peri-urban areas. Plants are cultivated in a nutrient rich solution which passes through an inert planting medium. - Organoponicos

These gardens are located in vacant lots in urban and peri-urban areas where the soil is not cultivable, thus cultivation takes place in raised beds or concrete containers. Many Popular Gardens are of this type because they are located in areas where the soil is of poor quality or contaminated (Taboulchanas, MES 2001).

Cienfuegos is the capital of the province of Cienfuegos and is located in the south central part of Cuba. Approximately 300,000 people live in the province of Cienfuegos while the city has a population of 120,000. The city is a marketing and processing center of a region that produces sugarcane, tobacco, coffee, rice and rum. Cienfuegos is Cuba's leading sugar export port as well as a major fishing port (*GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT CIENFUEGOS).

In 1998 and 1999, Cienfuegos won the national award for best urban agricultural production. Hence, Cienfuegos is considered the "urban agriculture" capital of Cuba. According to the latest national statistics, the organoponicos of Cienfuegos produce over 95 grams of fresh vegetables per capita per day (Taboulchanas, MES 2001).

ContentsContents

Cultivation Methods and Production

Cultivation takes place inside containers or raised beds filled with an organic matter and soil mix. The organic matter

is usually transported to the city from rural or peri-urban farms.

The cultivation methods are based on the principles of organic agriculture. The success of these gardens is attributed to the use of few external-inputs, the application of agroecology principles and their reliance on locally available resources (Altieri et al., 1999). Each organoponico has a cantero that is dedicated to the production of worm humus. After harvesting, residual plant materials are added to the worm compost-cantero and transformed into humus (Taboulchanas, MES 2001). |

Animal manure is another source of material for the worm composts. As a result of the Special Period many horse drawn buggies have replaced automobiles for public transportation leading to manure production within urban areas. Composted manure is added to the canteros as a natural fertiliser (Taboulchanas, MES 2001).

The organoponicos follow an integrated pest management approach that is based on a wide range of physical, biological and cultural practices (Table 2) . The government controls the use of chemical pesticides and fertilisers, which are used occasionally and only in situations when biological and cultural practices have failed.

Various vegetables, condiments and medicinal plants provide the bulk of the produce cultivated in the gardens (Table 3).

ContentsA general concern exists that once the Special Period is over (after the embargo is lifted), Cuba will revert to chemical intensive agriculture and its dependence on foreign food imports will increase (Altieri et al.,1999, Chaplowe 1998). Many scientists, farmers and politicians in Cuba have realised the benefits of urban agriculture (Table 4) and sustainable agricultural practices, and are making efforts to ensure the future of these gardens. International recognition of this movement may also aid in its continuation. In December of 1999, the Swedish Parliament awarded the Cuban Farming Association the "Alternative Nobel Prize" otherwise known as the "Right Livelihood Award" (Warwick, 1999).

ContentsSome Key Facts and Figures

Table 1. Yearly production figures for Cienfuegos.

| Production of organoponicos in the province of Cienfuegos | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production per year (tons) |

261 | 1,290 | 3,999 | 7,732 | 13,350 | 14,868 |

| Yields (kg/m2) | 5.43 | 16.2 | 19.57 | 20.41 | 25.43 | 26.5 |

Table 2. Integrated Pest Management Practices used in organoponicos (Altieri

et al., 1999; Taboulchanas, MES 2001).

| Crop rotations and inter-cropping Crop rotations and inter-cropping are important practices in the organoponicos. It is recommended that at any given time there should be at least 15 varieties of crops in every organoponico and gardeneners are encouraged to follow crop rotations and cultivate more than one crop in each cantero. |

| Biological control in the form of entomopathogens, fungi and bacteria This involves the application of bacteria, fungi and viruses for the control of pests. Examples include Bacillus thuringensis (bacteria) for the suppresion of various lepidopteran insect pest species and Trichoderma harzianun for the control of various bacterial and fungal diseases. |

| Beneficial insects and antagonists Various beneficial insects are released in the organoponicos including Chrysopa spp. for the control of aphids and leafhoppers. Antagonists are micro-organisms that protect plants from pathogens |

| Planting and application of botanical pesticides Solutions are prepared from insecticidal plants and applied to infected crops. Some insecticidal plants include Neem (Azadirachta indica), which is effective on a wide range of insect pests and Solasol (Solanum globiferum), which kills slugs and snails. |

| Insect traps There are various innovations that Cubans use to attract and trap pests such as yellow boards coated with a sticky substance. Another trap is made by setting out trays of beer and salt that attract snails and then drown them (Altieri et al. 1999). Crops such as Sorghum are planted around the periphery of the organoponicos or the canteros to attract beneficial insects and detter insect pests from feeding on the main crops. |

| Tillage to reduce the incidence of nematodes After the crops are harvested, the canteros are tilled and left to dry in the sun to rid of nematodes. |

Table 3. Most common crops found in organoponicos (Taboulchanas, MES 2001).

Rainy Season |

Dry Season (November to April) |

All year around |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Table 4. The Benefits of Urban Agriculture (Murphy, 1999).

Social Benefits

|

Ecological Benefits

|

Important Terms

- Beneficial insects

- Predatory or parasitic insects that attack agricultural pests.

- Canteros

- Raised container beds usually made of cement blocks and filled with compost and soil. They are 1-1.2 meters wide and 15-44 meters long.

- Container beds

- Raised beds that are enclosed by cement or wood.

- Cuba Democracy Act (1992)

- This Act extends the US trade embargo to overseas subsidiaries of US firms. It also prohibits ships that have docked in Cuba in the last 6 months from entering US ports (Chaplowe, 1998).

- Entomopathogens

- Organisms such as bacteria and fungi that are insect pathogens.

- Helms-Burton Act (1996)

- Officially known as the "Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act" it was named after its creators, the US Senator Jesse Helms and House Representative Dan Burton. The Act further tightens the 37-year-old US blocade against Cuba (Warwick, 1999) .

- Raised Bed

- A mound of prepared soil, approximately 15-20 cm high.

- Special Period

- The Special Period refers to Cuba's economic crisis that began in 1989 by the dissolution of its main trading partner, the Soviet Union. It has been labelled as the "Special Period in Peacetime" because measures were taken that are normally limited to wartime, such as planned blackouts and the use of bicycles for mass transportation.

- Worm Compost or Vermiculture

- This type of composting involves the use of earthworms, typically Eisenia foetida for converting plant wastes and manure into humus.

Useful Literature

Useful Links

(http://ag.arizona.edu/OALS/ALN/aln42/resources42.html) Katherine Waser, Comp. (1997, Fall/Winter ; Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)

This site was compiled and annotated by Katherine Waser. It contains links to useful web-sites, online articles and books on urban agriculture.

(http://www.fao.org/waicent/faoinfo/agricult/) Food and Agriculture Organization, Spons. (2001, Februuary 1 ; Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)

Recent information regarding the developments in urban agriculture worldwide.

(http://www.foodfirst.org/cuba/) Institute for Food and Development Policy, Spons. (2001, February 1 ; Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)

Articles and news on urban agriculture in Cuba; also information on Food First's events and programs related to urban agriculture.

(http://www.idrc.ca/cfp/reading_e.html) Internationoal Development Research Council, Spons. (2000, July ; Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)

This site contains numerous articles and reports about urban agriculture worldwide.

(http://www.cityfarmer.org) City Farmer, Spons. (February 10, 2001 ; Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)

These notes were initiated in 1978 by City Farmer. There are links to web sites on urban agriculture.

Cited Literature and Links

(http://www.cityfarmer.org/cubacastro.html) Dr. Alejandro Socorro, Maint. (1999, February 2; Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)

(http://www.cuba-casa.com/generalinfo.html) City of Cienfuegoos, Cuba, Spons. (Viewed Feb. 12, 2001)