|

Possible Impacts of Highway 113 on the Proposed

Blue Mountain/Birch Cove Lakes Park and the Need for Strengthened

Protection of the Park and the Adjacent Resource

Land/Natural Corridor Area. A

submission to Environmental Assessment Branch, Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Labour, 5151 Terminal Road, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J

2T8 e-mail: ea@gov.ns.ca Regional Planning Committee/ Regional Plan Public Hearing, Halifax Regional Municipality. c/o Clerk's Office, City Hall, 1841 Argyle Street, Halifax, NS B3J 3A5 e-mail: clerks@halifax.ca From:

Submitted

electronically and in hard copy on May 5, 2006 (Hy113DalComments.pdf) 1.

INTRODUCTION These comments are being submitted

to the Nova Scotia Department of

Environment and Labour (NSEL)

in response to a request for comments on or before May 5, 2006 on the Focus

Report for the Proposed Highway 113,

Class I Environmental Assessment

(N.S. Dept. Transportation and Public Works, March, 2006) and the associated Blue

Mountain/Birch Cove Assessment Study,

Final Report (Environmental Design

Management Limited report contracted by Halifax Regional Municipality, N.S. Dept. Transportation and Public

Works and N.S. Department of Natural Resources, March, 2006). NOTE

1 The

comments are addressed also to the Regional Planning Committee of HRM (Halifax

Regional Municipality) as they are pertinent to key aspects of protection for

the Blue Mountain/Birch Cove Lakes Park proposed in the HRM Regional Plan. This

plan was first reading in HRM Regional Council on 25 April, 2006. NOTE

2 i.

the undertaking is approved subject to specified terms and conditions

and any other approvals required by statute or regulation; ii.

an environmental-assessment report is required; or iii.

the undertaking is rejected." In

regard to the Regional Plan, a "Public Hearing to consider formal adoption of the Regional Plan, Regional

Subdivision By-law and amendments to the Municipal Planning Strategies and Land

Use By-laws of Halifax Regional Municipality necessary to implement the

Regional Plan will take place on: Tuesday, May 16, 2006 beginning at 1:00 P.M. Halifax Regional Council Chambers City Hall, 1841 Argyle

Street, Halifax." 2.

BACKGROUND The

Focus Report for the Proposed Highway 113 (hereafter referred to as the "Focus Report") addresses possibilities for increased

traffic in Halifax Regional

Municipality and a perceived need to construct a 9.9 km highway (45 m wide within a 150 m right of way)

connecting exit 3 on Highway 102 and exit 4 on Highway 103; The purpose of the proposed Highway 113

is to provide a more efficient means of travel for motorists between Highway

103 and Highway 102, that bypasses the Halifax Urban Core. It will also relieve

congestion on the Hammonds Plains Road. The proposed 4-lane divided highway

will go from Highway 103 near Exit 4 to Highway 102 near Exit 3. The

associated Blue Mountain/Birch Cove Assessment Study Final Report (hereafter

referred to as the "Assessment Study")

was conducted in connection with both the Focus Report and the HRM Regional Plan. Its focus is the delineation of a

regional park in the Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes area. Such a park is formally recognized in

the Regional Plan as the "Blue Mountain Birch Cove Lakes Park" and is one of

six new parks proposed in the Regional Plan for HRM. References below to "the

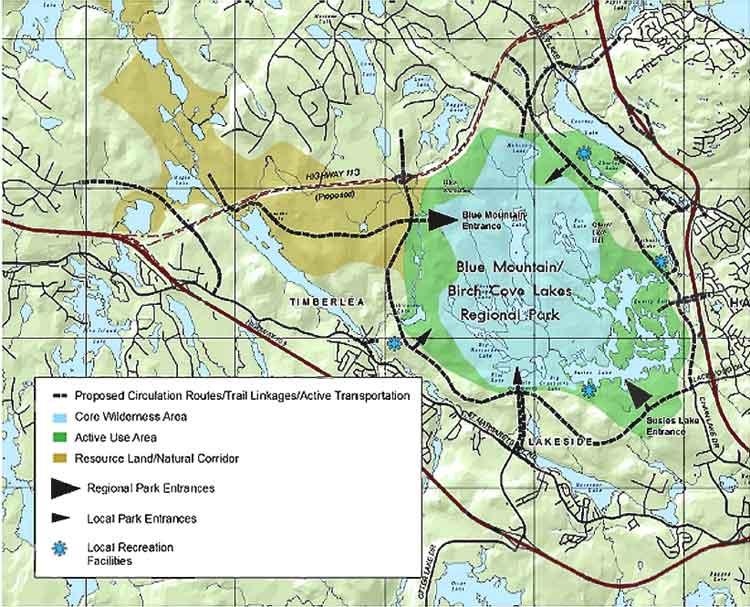

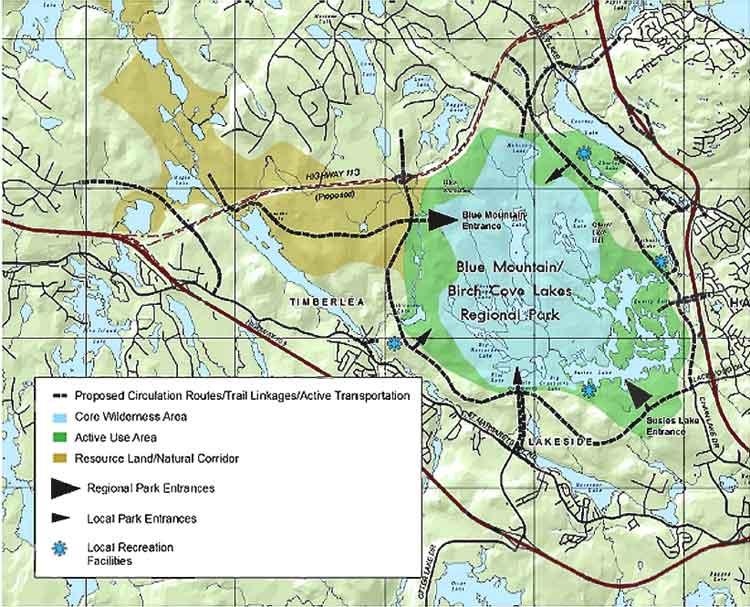

Park", refer to the proposed Blue Mountain Birch Cove Lakes Park. The Park

includes approximately 1450 ha of

land or 1700 ha of land and water. (For convenience, Fig. 5.1 from the

Assessment Study is appended to the end of this document; it shows the location

of the Park, the adjacent Resource Lands/Natural Corridor and the proposed

highway.) The Terms of Reference for both reports required that they address in some detail the

compatibility of the proposed Highway 113

with the Park and with

broader open space and wildlife corridor functions of the area. The

highway would not be built for at least 20 years. However, Š early planning for the highway is important as this

area of HRM is developing quickly and possible routes for a new road are very

limited. The majority of the proposed highway alignment crosses private land

and generally skirts existing development. Without corridor preservation the

majority of land required for the highway could be privately developed. The

expected result would be either the elimination of any options for the highway

alignment or a highway project that has higher construction costs, and causes

greater impacts on existing development and the environment. Some property has

been purchased in order to preserve a corridor for the highway where imminent

development would have prevented preservation of the landŠ Corridor

preservation work for the proposed Highway 113 began in 1998. The

overall conclusion reached in these reports in regard to ecological impacts

of Highway 113 appears to be that

while it is a potential threat to

natural values in the area, the direct impact is minimal and it can serve as "an effective barrier to future

encroachments by development"; further, "The Department [of Transportation and

Public Works] recognizes the potential requirement for wildlife corridors and

trail connections." 3.

COMMENTS The Assessment Study provides an excellent characterization of the many natural

values of the proposed Blue Mountain/Birch Cove Park area and their importance

for HRM. NOTE 3 We support the concept of an "Ideal Regional Park", which would

include a large Core Wilderness

area and a peripheral Active Use

area, also an adjacent Resource Land/Natural Corridor. The last mentioned is

not formally in the Park but it is integral to its ecological integrity and

important for movement of wildlife between the Chebucto Peninsula and the

greater mainland.

Such

a park would be a magnificent and perhaps unique resource including, as it

would, a protected, ecologically diverse wilderness area and providing

"Keji-like opportunities" within the confines of a major city. It will become highly valued by residents and visitors much as

historic properties and our seashore are today. In addition to its inherent

natural values and importance for protection of our water resources,

it could become a significant contributor to our economy through ecotourism. Perhaps more significantly for the

economy, it would give HRM "a lot

to crow about" as a superb place

to live. In the 21st century, access to "the outdoors" is an

important consideration for

many of the industries and

businesses and associated skilled workers and professionals we want to attract

and keep in this area. It is also highly appropriate for a capital region to

illustrate a firm commitment to protection of the environment and biodiversity

and a willingness to make the

kinds of sacrifices that are more commonly asked of rural residents of Nova

Scotia. It is highly prudent to make key decisions at this time given the

strong development pressure in the area and the increased costs from rising land prices that would be

associated with delaying decisions; further we will quickly lose many options as highways and

residential and commercial developments impinge on areas that are now

wilderness or quasi-wilderness. Indeed we are very fortunate in being able to

make the choices presently before us. There

are, however, several concerns in these regards. One arises

primarily from significant omissions in the reports related to potential

impacts on the ecology of the area,

and two have more to do with the legalities and practical difficulties

of protecting important

ecological features of the area.

Consideration of the likelihood of dramatically altered traffic demands and

patterns associated with rapidly rising fuel costs is an additional omission

that is not cited here but we understand is the subject of one or more other

submissions. Also, these comments

focus on a few issues, not all

possible issues, related to the ecology of the area. Concern

No. 1: The reports do not adequately address potential

negative impacts of the highway on ecological functioning of the area, nor do

they adequately address highway design features to mitigate such effects. Except

for impacts on wildlife corridor functions, the Focus Report and Assessment

Study do not discuss in any detail, possible direct negative impacts of the

highway beyond the right-of-way boundaries on either the Park itself, or on the

adjacent Resource Lands/Natural Corridor area. There is substantive scientific literature on this topic.

The following is an example: The Ecological Road-Effect Zone of a

Massachusetts (U.S.A.) Suburban Highway Richard T. T. Forman* and Robert D.

Deblinger, Conservation Biology 14: 1523-1739 (2000) Abstract: Ecological flows and biological diversity

trace broad patterns across the landscape, whereas transportation planning for

human mobility traditionally focuses on a narrow strip close to a road or

highway. To help close this gap we examined the "road-effect zone"

over which significant ecological effects extend outward from a road. Nine

ecological factors—involving wetlands, streams, road salt, exotic plants,

moose, deer, amphibians, forest birds, and grassland birds—were measured

or estimated near 25 km of a busy four-lane highway west of Boston,

Massachusetts. The effects of all factors extended >100 m from the road, and moose corridors,

road avoidance by grassland birds, and perhaps road salt in a shallow reservoir

extended outwards >1

km. Most factors had effects at 2–5 specific locations, whereas traffic

noise apparently exerted effects along most of the road length. Creating a map

of these effects indicates that the road-effect zone averages approximately 600

m in width and is asymmetric, with convoluted boundaries and a few long

fingers. We conclude that busy roads and nature reserves should be well separated,

and that future transportation systems across landscapes can provide for

ecological flows and biological diversity in addition to safe and efficient

human mobility. The

Assessment Study correctly identified

the importance of preserving wildlife corridor functions in the area,

including areas to the west

of the proposed park as (i)

a corridor for movement of wildlife between the Chebucto

Peninsula and Mainland Nova Scotia; The Blue Mountain/Birch

Cove Lakes area occupies a strategic location as the connecting green

space/wilderness area at the "pinch point" between approximately 22,000

hectares of undeveloped land on the Chebucto Peninsula and the greater mainland

of central Nova Scotia. The pinch point of the Chebucto Peninsula extends

approximately 18 kms between the Head of St. Margaret's Bay east to the Bedford

Basin, the widest section of the Blue Mountain/Birch Cove Lakes Study Area is

approximately 10 kms across this same corridor leaving only 8 kms of land

connecting the Chebucto Peninsula to the greater mainland. (Assessment Study,

p.24). (ii)

a corridor and/or habitat for migration of species into the Park, necessary for

the long term maintenance of the current level of biodiversity: It is important to note that while it may be

determined in the future that connectivity is not be required at a provincial

level of concern between the two large Crown parcels, the proposed Blue

Mountain/Birch Cove Lakes Park should still be connected to adjacent resource

lands. This connectivity is necessary to maintain the diversity and species

richness within the park boundary. As human use of the park intensifies the

pressure on individual species will increase, and many species will slowly die

out if there is not a ready population that can easily re-populate the park on

a regular basis. In addition, without connectivity the genetic pool within the

park may become limited over time for species without a sufficiently large

population. Connectivity also helps the park be more resilient to disturbances

such as a fire, hurricane or other natural disaster. Maintenance of species

diversity within the proposed park area over the long term will likely require

connectivity to at least one resource area and preferably two. (Assessment

Study, p. 46) Fragmentation

of contiguous wild (or largely unmanaged)

landscapes is the major cause of species loss globally and locally over

the last century. This is only

partially due to loss of habitat per se.

Today, professional ecologists talk about "the flux of nature" rather than

a " balance of nature", recognizing that populations of different species are

not static; the norm is for populations to fluctuate over time and even to go

locally extinct due to natural cycles and natural or manmade catastrophic

events such as fire and disease.

Thus, immigration of

individuals into an area becomes critical for the long-term maintenance of a species in that area (and the same area also acts at times as a source of

immigrants for other areas).

Fragmentation of natural landscapes leads to loss of species in an

otherwise suitable area by eliminating the possibility for immigration or by reducing the rate of immigration below that necessary to

maintain a population over longer periods of time or at critical times. The degree of landscape

connectivity that is required to maintain a species in a particular area

depends on the species and local factors; in general, the larger the local area, the less sensitive it is to the

degree of connectivity with other areas, but of course a larger area would be

required to maintain moose than for example, a ground beetle. This

short discussion is offered to emphasize two points: (i) populations of all species, including, for example, plants and insects, and not just those of

the larger or more noticeable animals (deer, moose, frogs etc,) are sensitive

to reductions in the degree of connectivity of landscapes; (ii) regardless

of special passage-ways that might

be built into the design of the highway and that might be adequate for some, more

mobile species, there will be

reductions in overall connectivity, i.e. it is inevitable that a highway will

lead to some (negative) effects on connectivity and biodiversity within the

proposed park. The

connectivity issue is very significant in relation to the Park. A high degree

of connectivity is critical because of

the Park's relatively small size; maintenance of ecological integrity

over the longer term – especially if there are fires - will be highly dependent on

connectivity and immigration. That there will be fires, started by natural

processes or by humans, seems to

be a fairly safe prediction. (In fact,

much of the vegetation in quasi-wilderness areas of HRM consists of

early successional species that are either stimulated by fire (e.g, jack pine), or stimulated by release of

competition by fires (e.g., white

birch, large tooth aspen). In

regard to migration of species between the greater mainland and the Chebucto

Peninsula, connectivity is probably not highly critical for maintenance of

smaller and more numerous species in the Chebucto Peninsula, but it could be

for larger animals, e.g., moose, brown bear, deer, as noted in the Assessment

Study. NOTE 4 Of particular

concern is the fact that highway 113, in the absence of specific design

features, would eliminate two of the three existing "key opportunities" that

facilitate movement of such

wildlife between the Chebucto Peninsula wilderness areas and the Bowater Mersey

lands north of Hammonds Plains Road (Assessment Study p. 45; Appendix A: Figure

20). These

effects and how they will be dealt with are not addressed in any detail in the

Focus Report or in the Assessment Study; rather it is recommended simply that

"highway design that facilitates the movement of a wide variety of plants and

animals should be consideredŠ" and

TPW comments that In consultation with DNR, the provision of passage for

a variety of species will be considered in the design of the structure crossing

the Maple Lake/Frasers Lake watercourse; in addition, four water crossings will

be required over Fishers Brook and Stillwater Run; two of these are fish

habitat; avoidance of fish habitat damage and provision of fish passage must be

provided for these crossings; in the design of these crossings consideration will

be given to providing sufficient width and span height to allow the passage of

all but the largest wildlife species, which would provide connectivity in areas

with less human presence than the Maple Lake/Frasers Lake crossing may have. That

on its own might be reassuring if the design of wildlife corridors through

highways was a well developed science. It isn't. There is a large literature in this area. An authoritative

recent text on Ecosystem Management notes possible pitfalls of designed

corridors and comments: At present we do not understand corridors well enough

to evaluate these possible pitfall. In the years to come, after more movement

corridors have been designed, implemented, and monitored for success, we will

better understand their potential advantages and disadvantages. In the meantime

we need to try and reconnect landscapes that were historically connected and

that have become fragmented though human use. (GK Meffe et al., Ecosystem Management: Adaptive,

Community-based Conservation Island Press, 2002) Further

there have been many practical difficulties with maintaining wildlife corridors

through highways, and the more

elaborate, possibly more effective,

corridors are very expensive. These issues have not been addressed in

relation to the proposed highway. Concern

No, 2 Insufficient

consideration is given to the need to protect the Resource lands/Natural

Corridor area to the west of the

proposed park and highway, and

for immediate protection of the entire area from development. Even

if the highway were constructed with effective wildlife passageways, or even if

it were not constructed at all, the wildlife corridor lands and significant

wetlands and other water resources to the west of the proposed park and highway

– as well as the Core Wilderness Area and the peripheral Active Use Area - are potentially subject to fragmentation and physical

disruption through development of

existing private holdings.

Further, statements in the focus report give some concern that tradeoffs

of crown land in this western area might be made with local developers in

exchange for private lands currently held within the planned highway right of

way. In

the Assessment Study it is noted: Connecting the park to resource lands could require

management control and/or acquisition of critical parcels in the area between

Timberlea, Kingswood, and Hammonds Plains, as indicated in Figure 20 of Appendix A entitled Connectivity. However,

there is not much further discussion of this issue, which is clearly critical

for connectivity. Understandably

the Focus Report, coming from the Department of Transportation and Public

Works, focuses on securing rights

of way for the Highway. The

discussion reveals the sorts of tradeoffs that have occurred before: Over time, some of the crown land has

been traded off to developers for other properties or assets resulting in some

erosion of the crown land holdings.

As well, development

pressure in the area is raising the cost of purchasing private land that might

be added to the crown land for protection [ of the proposed Park] and actual developments are gradually

encroaching on the proposed protected [Park] area; similarly, these pressure

are raising the costs of private land that would need to be purchased to build

the connector highway or, through development, could directly encroach on the

proposed highway. It is clear

from various statements in the reports that there is good reason to be

concerned about development pressures and that possible land swaps in favour of

the highway would detract from the western corridor area, e.g., on p. 33 of the Assessment

Study it is noted: €Mapping of developed and developable private land

indicates the rapid rate of development and the likelihood of development on

private lands which would preclude construction of Highway 113, if the corridor

were not established well before planned highway construction; € Developers have modified their plans based on the

publication of the plans for Highway 113, confirming the need to establish the

corridor and identifying a need to resolve the issue, so that developers can

proceed. On page 50

it is noted: The Crown

and private lands lying to the south and west of the generalized park area form

an important natural corridor, providing connectivity to the more extensive

Crown and Bowater lands to the south and westŠ A critical link in this corridor

is at Maple Lake/Frasers Lake where the proposed Highway 113 corridor crosses

the lake system. The highway will be located on one of the few remaining

"necks" of land available for species movement. The Piercey Investors

subdivision development on their lands to the west of the lakes may present a

significant complication for this initiative. Also,

large sections in the western area are rated at the two top levels in the

suitability scale for unserviced

residences (Fig 12 of the Appendix to the Assessment Study), which would add to pressure to trade off these area

off for private lands needed for the Highway right-of-way. Clearly the same development pressures that threaten the right-of-way

for Highway 113, also threaten the maintenance of or procurement of additional

lands to ensure the integrity of

the resource lands/natural corridor west of the proposed park and

highway 113 as well as the Core Wilderness area and the peripheral Active Use area. The difference is that

procurement of land to secure a right-of-way for Highway 113 began in 1998 and

is the focus of TPW concerns

(understandably), while equivalent

consideration and priority has not

been given to ensure the integrity of

the western Resource lands/Natural Corridor area or even of the Core Wilderness area and the peripheral Active Use area of the

Park proper. The highway is promoted as "an effective barrier to future encroachment

[of the Park] by development". However, the protection afforded by the highway is not a physical barrier but rather a

legal barrier associated with procurement of the right of way 20 or years

before a highway might even be considered. There seems no logical reason why,

in the same context, the same kind of insurance should not be applied to

securing the integrity of the western Resource Land/Natural Corridor area as

well as that of the Core Wilderness area and the peripheral Active Use area of the Park proper. Future generations will thank us for leaving all options fully open at

a time when we still have the choice to do so, not just those related to the

highway. Concern

No. 3 There is some

ambiguity in the proposal to maintain a large core wilderness area in the Park,

but not to give it wilderness area status under the Wilderness Areas Protection Act. Giving

such status to the core wilderness area would be the best way to protect it,

while still allowing the core area recreational activities discussed in the

Assessment Study. This designation

would be very appropriate in the context of this area being in an urban capital

city. It would be an invaluable educational tool for residents of HRM, an

additional "crow factor" for HRM, and the best practical protection we could

give to the most valued features of the Park. 4.

CONCLUSION The

Assessment Study is excellent in many regards, but is seriously deficient in

regard to possible direct negative impacts of the proposed highway beyond it's

the right-of-way and in regard to the limitations and challenges of mitigating

effects of the highway on corridor functions. The need to protect the western

Resource Land/Natural Corridor area is cited, but is not emphasized and is not

given due consideration in the Focus Report. The Assessment Study indicates

that the proposed boundaries are not fixed, but are adaptable which, given the

development pressure in the area and the high priority given to procurement of

right of way for the highway, raises concerns about possible opportunistic and

irreversible development in key

areas and about possible tradeoffs of land that would compromise the integrity

of the Park and the western Resource Land/Natural Corridor area. Thus we

suggest: ·

If the highway option is not rejected, a full

environmental review should be required.

At the minimum, the necessity to secure the western Resource

Land/Natural Corridor as well as the Core Wilderness area and the peripheral Active Use area should

be given as much emphasis as that given to procurement of lands for the highway

right-of-way. ·

Regardless of whether the highway option is rejected or

maintained, the integrity of the western resource Land/Natural Corridor area,

as well as that of the Park proper, need to be secured; an immediate, unequivocal

moratorium should be placed on any further development in the entire area. ·

The benefits of giving the Core Wilderness area

protection under Wilderness Areas Protection Act should be seriously considered. NOTES 1. The pertinent announcements and documents were accessed

at a Nova Scotia Department of Environment and Labour webpage: Highway 113

Project at: www.gov.ns.ca/enla/ea/highway113.asp The relevant documents are available as downloadable PDF

documents, including: Focus Report (1.1

mb) www.gov.ns.ca/enla/ea/highway113/Hwy113_FocusReportPublicNotice.pdf The text of the Assessment

Study is contained in Appendix B1 (8.3 mb) and Appendix B2

(8.1 mb): www.gov.ns.ca/enla/ea/highway113/Hwy113_app_b1.pdf

www.gov.ns.ca/enla/ea/highway113/Hwy113_app_b2.pdf Terms of Reference, detailed

GIS-based maps, the traffic

projection study and other relevant documents are also accessible via the

Highway 113 Project webpage. For convenience, Assessment Study

Fig. 5.1 showing the location and boundaries of the proposed Blue

Mountain/Birch Cove Lakes Park and the adjacent Resource Lands/Natural Corridor

area and the proposed highway is appended to the end of this document. 2. See HRM Regional Planning for HRM at www.halifax.ca/regionalplanning/

The full Plan is available at www.halifax.ca/regionalplanning/FinalRegPlan.html

Map 13 listed on that page shows the location and boundaries of the

proposed Blue Mountain Birch Coves Lake Park and the adjacent Resource

Lands/Natural Corridor. 3. Public

Interest Group Values for the Blue Mountain/Birch Cove lakes area cited in the

Assessment Study include €Last piece of

publicly owned wilderness in this part of HRM € Largest area without

roads near the Halifax urban concentration € Known populations of

endangered mainland moose (Chebucto population) € Contains 22 lakes

and ponds many of which are entirely surrounded by public land € Contains headwaters

of the Kearney Lake, Papermill Lake, and Nine Mile River watersheds € Diverse mosaic of

ecosystem types, including numerous forest types (e.g., white pine, red spruce, red

oak, yellow birch, white birch, poplar, red maple, black spruce, mountain ash),

wetlands, barrens, aquatic areas, rivers, rapids, cliffs € Presence of southern

coastal plain flora species adjacent to sub-arctic alpine plants. € Several stands of

old-growth Acadian forests, including exceptional stands of old red oak, old red

spruce, and old white pine (with understories of similar species compositions). € Presence of a

naturally rare stand of jack pine (fire dependent ecosystem) € Presence of at least

two rare granite barren ecosystems dominated by tolerant red oak species (red oaks

usually occur in relatively nutrient rich areas) € Numerous granite

barren ecosystems, and associated rare arctic-alpine plants (e.g., Greenland

sandwort (Arenaria groenlandica)) € Numerous wetlands with

examples of bogs, fens, swamps, and shallow water areas € Significant

wetlands, including the "promised lands," Stillwater Run, and the lakeshore fens of the

Birch Cove Lakes canoe loop € Highest point of

land in Metro Halifax ("Blue Mountain Hill")14

with associated windblown treeless

area and sub-arctic alpine plants € Abundance of bird

species, with 146 different species recorded by the Nova Scotia Bird Society

(e.g., osprey, loon, bald eagle, blue heron, mourning dove, American kestrel,

Swainson's thrush, pileated woodpecker, great-horned owl, cedar waxwing, etc.)

owing to geographic location and habitat diversity. Many of these are breeders.

Some are recognized as rare species. 4. Some

argument is made that the Mainland Moose numbers in this region are so low (approximately 30 centered on the Chebucto Peninsula, and

20 in the Ship Harbour area) that we can really not make a strong case for

extra-ordinary measures to protect them;

the survival of mainland moose is dependent on maintenance of the larger

concentrations elsewhere. That may be true in a strict sense. However, they do

or could have strong symbolic value;

as a large, rather elusive

species, real efforts made to protect the Halifax County moose will

protect many other species and habitats. The Florida panther is an appropriate

analogy; there are only approximately 50 of these animals left in the whole

state of Florida, but extra-ordinary efforts, highly supported by the

public, are being made to conserve

them. This could hardly be justified

economically or even by wildlife biologists were it not that the efforts to conserve the Florida

panther - including protection of key corridor areas – also protect key

habitats for many other species. In Nova Scotia the Mainland Moose could be our

Florida Panther! Additionally, by giving proper protection to moose in the

capital area, there will less resentment of protection measures in rural areas.

The next

page is Figure. 5.1 (Proposed Blue Mountain/Birch Cove lakes Park) from the

Assessment Study (p. 47). |